When Do Mares Ovulate?

Since mares are seasonally polyestrus, they experience regular estrous cycles during late Spring, Summer and early Fall, and none during the Winter. These cycles are controlled by hormones, which respond to increases or decreases in daylight duration with the onset of the seasons.

The typical mare cycles regularly between March and October, with each estrous period being an average length of twenty-one days.1

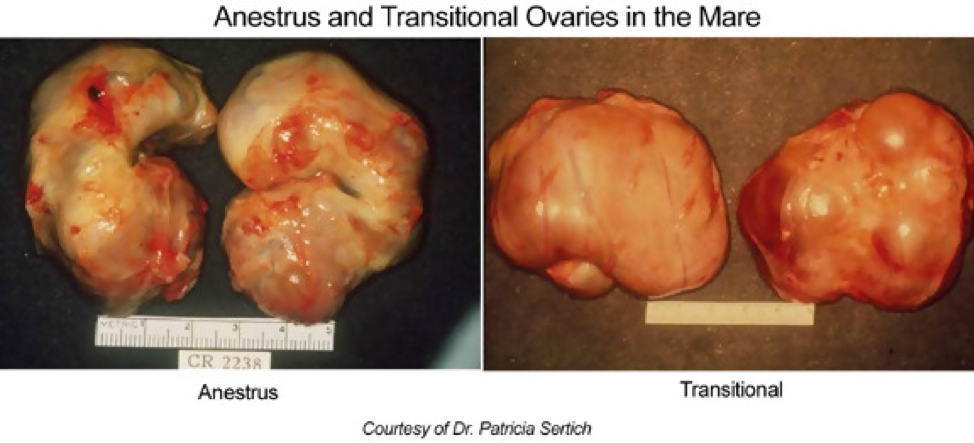

Anestrus is seen during the winter when daylight length is short. During anestrus, the uterus is flaccid, and the ovaries are inactive with no significant follicles or corpora lutea. The cervix may be closed but not firm and tight, or it may be thin, short, and dilated. As the length of daylight increases, mares undergo a vernal transition and the ovaries become active, with numerous large (>25 mm) follicles. The cervix and uterus have minimal tone. Mares have three or four prolonged intervals of estrus (periods of sexual receptivity to the stallion) during the vernal transition, but ovulation does not occur.2

Estrus, or heat, is the period of the reproductive cycle when the mare ovulates and, if bred, is likely to conceive. Estrus is also the time when the mare is receptive and will accept the stallion. The average length of the estrous cycle, or the period from heat period to the next heat period, is 21 days, but the estrous cycle can vary from 19 to 26 days. The duration of estrus is five to seven days (actually about six days), but it can vary from two to 10 days. The first heat following foaling is referred to as foal heat. Foal heat typically occurs six to nine days after foaling, but it may be as early as five days or as late as 15 days.3

According to Dr. Sertich and the bulk of the literature, mares have two follicular waves each cycle.

The first wave of follicular development occurs during diestrus, and these follicles become atretic. The second wave occurs after luteolysis and is associated with estrus. Early in estrus, the endometrial folds of the uterus are edematous, but the edema wanes as ovulation approaches. Usually, one follicle becomes dominant and ovulates when it is ≥30 mm in diameter. The dominant follicle enlarges and then softens just before ovulation. The oocyte is released through the ovulation fossa.2

Manipulation of the Estrous Cycle

For purposes of scheduling breeding and for the behavioral control of intact mares, it is often desirable for horse owners and managers to employ methods of reproductive management, or manipulation of the estrous cycle. Shortening of the estrous period in mares is one such manner of regulation.

Horse owners and managers have long relied upon manipulation of the photoperiod for the reproductive management of mares. In order to bring the mare into estrus, many horse owners and managers start with manipulation of the light cycle. "We start with the basic premise that the key to reproduction is light... [H]orsemen literally can trick Nature into moving out of its natural rhythm with the administration of artificial light."4

Pertaining to manipulation of the photoperiod, Dr. Sertich offers the following recommendations:

After winter anestrus and the vernal transition, cyclicity naturally starts sometime in the spring, when breeding can begin. Because changes in the mare’s genital tract are seen in response to the length of daylight, the onset of ovulation and subsequent regular estrous cycles—and thus, the onset of the breeding season—can be hastened by exposing the mare to 16 hr of light per day; 8–10 wk are required for mares to respond. If the breeding season is scheduled to begin February 15, mares should be exposed to daily supplemental artificial lighting starting on December 1.

Mares need to experience a natural photoperiod of decreasing length of daylight in the fall. Mares can then be abruptly exposed to 16 hr of light each day, or the supplemental light can be gradually increased to a 16-hr day throughout 60 days. In an abrupt lighting program, mares living in natural daylight are exposed to supplemental light from ~4:30 pm until 11:00 pm daily. In a less expensive, energy conserving, stepwise program, mares can be exposed to 3 hr of supplemental light in the evening the first week of December, and then the supplemental light is increased by 30 min each week until mares are exposed to 16 hr of light each day. An automatic timer aids compliance and saves on labor.

The supplemental light must be added at dusk; light added in the morning before dawn is not effective. A minimum of 10 foot-candles (107 lux) of incandescent or fluorescent light is necessary. The amount of light should allow one to comfortably read newsprint. Mares can be stimulated individually in a stall or as a group in a lighted paddock.2

In shortening the estrous cycle, appropriate manipulation of the photoperiod is used according to the related breeding program, however chemical regulation is essential to achieve desired outcomes. Buserelin and deslorelin have been widely used in the chemical regulation of mares, but several studies, as well as many veterinarians and compounding pharmacies have achieved superior results using several such compounds in combination.

Equine Breeding Products

Equine Breeding Products

You can find equine breeding products in our online store. Login to your account to view prices and purchase or create an account. Please note you must have a valid veterinarian license to create an account. If you do not, please forward our information to your veterinarian.

1Kuhns, B. Brood Mare Management, Modern Veterinary Practice, Volume 55/Number 5, p.359, May, 1974.

2Sertich, P., DVM. Reproductive Cycle in Horses, Merck Veterinary Manual, 2019.

3Griffin, A. Horse Breeding Behavior, New Technologies for Agriculture Extension grant no. 2015-41595-24254 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, July, 2019.

4Sellnow, L. Regulating Estrus in Mares. The Horse, Dec. 1998.

About NexGen Pharmaceuticals

NexGen Pharmaceuticals is an industry-leading veterinary compounding pharmacy, offering sterile and non-sterile compounding services nationwide. Unlike other veterinary compounding pharmacies, NexGen focuses on drugs that are difficult to find or are no longer available due to manufacturer discontinuance or have yet to be offered commercially for veterinary applications, but which still serve a critical need for our customers. We also specialize in wildlife pharmaceuticals, including sedatives and their antagonists, offering many unique options to serve a wide array of zoo animal and wildlife immobilization and anesthesia requirements.

Our pharmacists are also encouraged to develop strong working relationships with our veterinarians in order to better care for veterinary patients. Such relationships foster an ever-increasing knowledge base upon which pharmacists and veterinarians can draw, making both significantly more effective in their professional roles.