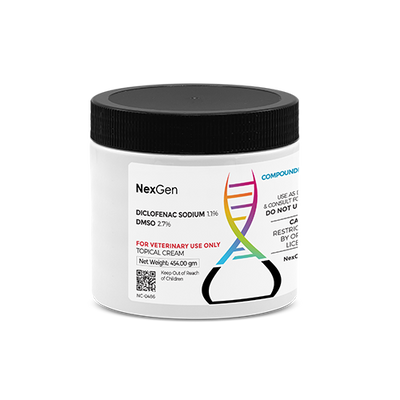

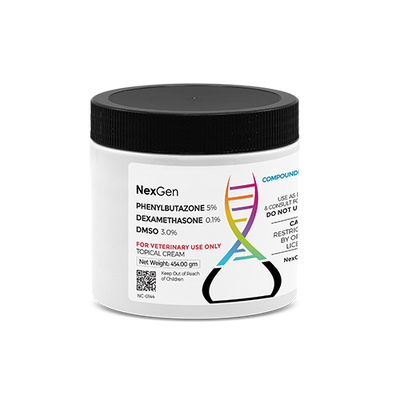

3-D Cream (Diclofenac Sodium, Dexamethasone, DMSO), Topical Cream, 16oz

Login for pricing

- Brand

- Mixlab

- SKU:

- NC-0120

3-D CREAM ( Diclofenac/ Dexamethasone/ DMSO)

Arthritis is an extremely common condition in horses, and one that frustrates horse owners in terms of short- and long-term management. “Arthritis” simply means an inflammation of the joints. In horses, several types of arthritis can occur, with causes ranging from infection to age and years of athletic use.1 Generally, horse owners and others tend to use the word “arthritis” in lieu of osteoarthritis, which is a chronic, progressive, painful degeneration of the cartilage lining the ends of long bones inside joints, as well as the underlying bone and soft tissues. This is as opposed to such conditions as rheumatoid arthritis in humans, which is actually an autoimmune disease.

Once known as degenerative joint disease, osteoarthritis (OA) can affect any articular joint (a joint where two cartilage-covered bones meet). In performance horses, OA is often thought of as affecting joints in the limbs—hocks, knees, stifles, and fetlocks. Signs of OA often include heat, swelling due to excess joint fluid, lameness/pain, stiffness, deformation caused by bony changes, and crepitus—that popping, grinding, and crackling sound and sensation in an affected joint.1

Osteoarthritis: Not Just for Old Horses

When a horse presents as stiff or lame, the owner will often assume that the horse has arthritis, although this may not be the case. As regards this condition, people typically think of older horses despite the fact that, as with human beings, OA is not the exclusive domain of geriatric horses. Studies show 60% of all equine lamenesses are related to osteoarthritis,2 which covers a majority of horses that do not qualify as geriatric.

Because there is no cure for OA, its management and prevention continues to be of great concern for equine practitioners and researchers. “Osteoarthritis is a disease of joints with multifactorial causes that results in the progressive degradation and destruction of articular cartilage: the very thin layer of highly specialized connective tissue lining the ends of the long bones where they join. In young horses OA is predominantly trauma-related.”2

Particularly in performance horses, repeated exposure to athletic trauma, loss of stability or development of joint abnormalities and remodeling and microfracture in the bone underlying the articular cartilage can all negatively impact normal articular cartilage. Similarly, normal forces on cartilage damaged via synovitis and capsulitis, normal aging processes, and conditions such as osteochondrosis can similarly affect the cartilage in joints to their detriment.

OA’s Far-Reaching Effects

According to the American Horse Council, the horse industry has a total impact of more than $100 billion on the U.S. gross domestic product.2 Such losses not only affect horses and their owners, but also more than 4 million people associated with the industry. Treatment for OA not only includes direct (treatment-related) costs, but also indirect costs such as lost income due to time spent on the affected horse instead of working, lost leisure time, and increased time and expenditures managing the patient with OA.2 Those direct and indirect costs can pile up, especially with horses that develop OA at a young age.

OA is a progressive disease, and it has no known cure. Thus, the afflicted horse will have to endure the disease for the remainder of its life. In order to manage pain and discomfort, control swelling and prolong the horse's ability to function, treatment will become necessary at some point.

Once it has been determined that OA is the cause of a horse’s pain and discomfort (as opposed to other conditions presenting with similar symptoms), it is a good idea to attempt to gauge the arthritic horse’s pain levels. The most common method of assessing lameness is a veterinary lameness exam, generally using the American Association of Equine Practitioners’ lameness scale, as well as flexion testing and anesthetic blocks (regional or in the joint, if possible) to accurately determine the site of pain. Radiographs (X-rays) can reveal typical OA lesions.1 Horses with early onset OA often appear stiff when emerging from the stall or starting work, but after warming up, they appear much more comfortable. More severe signs—typically observed in more well-established cases of OA—can include swelling, heat, and persistent lameness.

Complicating the situation is the fact that people tend to assume a horse has OA because it is a common condition. Deciding that any horse has a particular medical condition and treating it without consulting a veterinarian however, can have dire consequences.

Treatment of OA in Horses

The medical treatment of osteoarthritis (OA) in the horse is one of the most utilized therapeutic regimens in the equine practice.4 It is important to understand the anatomy of synovial joints and the pathophysiology of the disease process to treat OA adequately. Once a thorough understanding of the disease process is comprehended the proper combination of systemic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), intraarticular steroids, viscosupplementation and chondroprotectants can be used to treat the disease and inhibit further progression of degenerative changes to the cartilage surface.3,4

The equine practitioner is faced with many choices for controlling inflammation in OA. At present, a multimodal treatment approach is advocated by many equine veterinarians and researchers. This includes:

-

Pain management via administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or corticosteroids

-

Intra-articular medications (hyaluronic acid, polysulfated glycosaminoglycans)

-

Intramuscular polysulfated glycosaminoglycans

-

Weight management

-

Non-weight-bearing exercises (e.g., swimming) and physical therapy;

-

Dietary modification (adding omega-3 fatty acids)

-

Oral joint health supplements (OJHSs) including glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, methylsulfonylmethane (MSM), avocado/soybean unsaponifiable extracts (ASU), etc.1

The administration of anti-inflammatory drugs (orally, topically, intravenously, or intra-articularly) is a mainstay in OA management. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as phenylbutazone are the most well-known and accessible treatments; however, clinicians have increasingly recognized safety concerns and encouraged alternatives.

Ankylosing Spondylitis in Horses

Spondylosis (Ankylosing Spondylitis) is a degenerative condition of the spinal column in horses. This degenerative condition causes back pain of varying degree in the equine which is generally displayed by the horse in behavioral changes rather than obvious pain responses.11 Back pain and behavioral changes exhibited by a horse may not always indicate spondylosis, but can also be the result of improperly fitting tack, poor training, heredity or other factors. With spondylosis, there is a degeneration of the bones of the vertebral column, leading to new bone spanning the disc between the vertebrae.

Symptoms of spondylosis in can include:

-

Decreased performance

-

Bucking or rearing

-

Biting or nipping

-

Stiffness or rearing when being mounted by a rider, which usually abates after exercise

-

Sensitivity to blanketing or brushing

-

Refusal or hesitation regarding jumping

-

Stumbling, tripping

-

Toe dragging (front or hind limbs)

-

Refusal to roll or lay down11

Since spondylosis is a degenerative condition, the age of the horse can be considered a causative factor in the attendant spinal degeneration. Since chronic back pain in horses can be caused by other factors, there are other potential causes that should be considered:

-

Injury or trauma

-

Arthritis from previous trauma or injury

-

Improperly fitting tack

-

Hereditary orthopedic defects

-

Muscle strain

-

Bone fractures

-

Systemic conditions (i.e., an unrelated condition or injury that causes sufficient discomfort to bring about a back injury)

-

Weight and riding position of rider(s)

Since the potential causes of spondylosis are quite varied, diagnosis of its specific cause or causes can be challenging. A thorough and extensive history of the horse will need to be provided for the veterinarian; this will provide the basis for the physical examination and any modifications deemed necessary by the veterinarian, who will probably order radiographic imaging will be done to assess any potential abnormalities.

Ultrasonic imaging may also be deemed appropriate to assess any soft tissue involvement that may be suspected. Sometimes, nuclear scintigraphy (bone scan) or thermography may also be utilized to get to the root cause of the back pain.12 In many cases, diagnosis is dependent upon a process of elimination of the potential causes of the back pain. Treatment for back pain will be dependent upon the final diagnosis obtained by the veterinarian.

3-D CREAM ( Diclofenac/ Dexamethasone/ DMSO)

Although glucocorticoids have been used to treat many conditions in humans and animals, dexamethasone has five primary uses with accompanying dosage ranges:

1) as a diagnostic agent to test for hyperadrenocorticism,

2) as a replacement or supplementation (eg, relative adrenal insufficiency associated with septic shock) for glucocorticoid deficiency secondary to hypoadrenocorticism,

3) as an anti-inflammatory agent,

4) for immunosuppression, and

5) as an antineoplastic agent.7,8

Note: The Association of Racing Commissioners International (ARCI) Uniform Classification Guidelines for Foreign Substances (UCGFS) Class 4 Drug.

As an anti-inflammatory glucocorticoid agent, dexamethasone is typically administered 2.5 – 5 mg (total dose) IV or IM for a 500-kg horse. As an adjunctive treatment of recurrent airway obstruction, dexamethasone is typically administered at 40 mg (total dose; NOT mg/kg) IM once every other day for 3 treatments, followed by 35 mg (total dose; NOT mg/kg) IM once every other day for 3 treatments, followed by 30 mg (total dose; NOT mg/kg) IM once every other day for 3 treatments; continue tapering until horse is weaned off this therapy (for a 500-kg horse).9

In one study, dexamethasone 0.05 mg/kg IM every 24 hours was as effective as inhaled fluticasone in reducing clinical signs, airway inflammatory cells, and bronchoprovocative histamine response in horses.10

DMSO is commonly used topically to treat inflammation in horses. It is a byproduct of paper production, and was originally created as an industrial solvent. DMSO is now approved for veterinary use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, although it is banned from some horse sports. DMSO works as an antioxidant, binding with free radicals that damage healthy cells. Trapping these free radicals slows the inflammation process. DMSO can be injected directly into a soft-tissue injury that is difficult to treat or that involves dense tissue. Additionally, veterinarians may administer DMSO orally or via IV to attempt to halt laminitis.5

In the 1960s, DMSO was considered a potential “miracle drug,” but shortly thereafter, the use of DMSO waned dramatically in the wake of safety concerns. DMSO gradually gained renewed acceptance after it was approved for use in horses in 1970. Today, many veterinarians and equine researchers view DMSO as not just a medication, but as a therapeutic paradigm unto itself. This is because DMSO’s action can help to potentiate other treatments as well as having its own discrete effects.

Where to buy 3-D CREAM ( Diclofenac/ Dexamethasone/ DMSO)

FOR RX ONLY: A valid prescription from a licensed veterinarian is required for dispensing this medication.

1Oke, S., DVM. What You Need to Know About Equine Osteoarthritis. In: TheHorse.com, July 2019. https://thehorse.com/164328/what-you-need-to-know-about-equine-osteoarthritis/

2Oke, S., DVM. Osteoarthritis: Not Just an Old Horse Disease. In: TheHorse.com, April, 2010. https://thehorse.com/154329/osteoarthritis-not-just-an-old-horse-disease/

4Goodrich LR, Nixon AJ. Medical treatment of osteoarthritis in the horse - a review. Vet J. 2006 Jan;171(1):51-69. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2004.07.008. PMID: 16427582.

5Kidd, J.A., et. al. Osteoarthritis in the horse. Wiley Online Library, 05 January 2010. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3292.2001.tb00082.

7Alvarez F, Kisseberth W, Gallant S. Dexamethasone, melphalan, actinomycin D, cytosine arabinoside (DMAC) protocol for dogs with relapsed lymphoma. J Vet Intern Med. 2006;20:1178-1183.

8Greenberg CB, Boria PA, Borgatti-Jeffreys A, Raskin RE, Lucroy MD. Phase II clinical trial of combination chemotherapy with dexamethasone for lymphoma in dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2007;43(1):27-32.

9Ainsworth D, Hackett R. Disorders of the respiratory system. In: Reed M, Bayly W, Sellon D, eds. Equine Internal Medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2004:289-354.

10Leguillette R, Tohver T, Bond SL, Nicol JA, McDonald KJ. Effect of dexamethasone and fluticasone on airway hyperresponsiveness in horses with inflammatory airway disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2017;31(4):1193-1201.

11Kontzias, A. Ankylosing Spondylitis. In: Merck Veterinary Manual, May 2020.

12Lo, Christine & Nair, Krishnan & Romanowski, Charles & Fawthorpe, Fiona & Lindert, Ralf-Björn. (2014). Horse’s tail in bamboo spine: The ‘cauda equina syndrome in ankylosing spondylitis’. Practical neurology. 14. 10.1136/practneurol-2014-000868.